If you can’t eradicate, regulate and take a big chunk out of the wages of sin while you’re at it.

Currently, the Internet has many legal issues. There are some elements which many do not consider suitable for the Internet at all. Financially, collection of sales taxes from state to state has never been settled. For moralists and many politicians, it is considered out of sufficient public scrutiny and particularly dangerous for the young. The usual treatment? Prohibition.

Lotteries have always been part of our colonial history. In 1754, Virginia authorized a lottery to fight the French and Indian War. In 1769, George Washington managed a lottery in Williamsburg. During our Revolutionary War, they raised money for fighting. After the war, they helped sustain the new and struggling country.

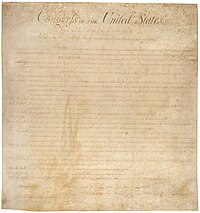

Lotteries have always been at war with causes, people, and politicians. Alexander Hamilton liked them, so I guess that his support generated strong opposition. In the decades since 1776, lotteries have gone boom or bust. They have been praised or banned. Only recently, since most states now have official lotteries, they have achieved a certain respectability. After all, they support good works, such as education.

Therefore, adding a new book, The Lottery Wars, to the Friends of 1776 library, seems timely and well-worth reading. The title describes the contents as “Long Odds, Fast Money, and the Battle Over an American Institution”. In spite of the millions who consider gambling a sin, it has never stopped.

This book makes for some very interesting reading. It is crammed full of facts including names and dates. It does not really write about gambling wars as a straight historical text. Rather, it focuses on winners and losers, who gambles and how, and the public fascination with those who win. What is that really like?

A great deal of The Lottery Wars focuses on the public side of lotteries, the business, including many pages exclusively on Joan Borucki, appointed California State Lottery chief in 2007. Her chief goal was to improve the whole financial position of the lottery, and therefore generate more revenue for the state, including education. The California lottery had been badly lagging. Better distribution of sales became very necessary. Tickets went into Big Retail. The $20 lottery ticket began to be accepted.

There is talk of privatizing the whole operation. States would get their money, up front, lots of it, but that would be it. Then the owner keeps the profits. There are a lot of financial and ethical issues with this proposal.

The book differentiates well between how official government regards the lottery and the players’ view. With government, you don’t consider sin, but marketing, growth, sales; it’s a business seminar. The player wants to know how much are the tickets, where are they, what are the prizes. A winner comes well-prepared with an attorney, tax accountant, financial advisor, who else knows what.

Groups, often employees, buy tickets together. I like this; there’s better organization and planning this way. More people have a chance to win something. The office football pool is a popular private lottery. You put your money in, if you win, you get everyone’s. I hope there are no expenses.

Do I gamble the state lottery? No, but I do participate in sweepstakes, a private lottery, run by Publishers’ Clearing House. This has gone on for years. There are good prices for popular magazines I sometimes order. Then I’m entered into the sweepstakes. Actually, I don’t have to order anything, just send in the entry. The payouts are quite high. Will I win? Are you kidding? But when I do, I’ve already made big plans on how to spend the money. – Renata Breisacher Mulry

The Lottery Wars: Long Odds, Fast Money, and the Battle Over an American Institution. Matthew Sweeney. Bloomsbury, 2009. 295 pp.

Buy Flags at Sears

Buy Flags at Sears